Nick Horween

Posted November 8, 2016

Interview by Andrew Chen

Photos by Alex Maier

The process of making leather is not an easy one. Hides are organic materials, and thus come in all kinds of shapes, sizes and conditions. Each hide needs to be soaked, pressed, tumbled, trimmed, tanned and oiled to produce a consistent end product. These processes require trained eyes and skilled hands; sadly, there aren’t too many of them left here in our country.

Founded by Ukranian immigrant Isidore Horween in 1905, Horween Leather Company has been tanning leathers in Chicago for over a century. Their leathers have been used on official Wilson NFL footballs and on coveted Alden and Allen Edmonds shell cordovan shoe styles for decades. They are also the last remaining tannery in their city, and one of a handful left in the United States. As Horween’s VP and Director of Quality, Nick Horween has been responsible for not only for overseeing the product but for communicating their increasingly unique vision to the outside market. In an industry focused on maximizing output and increasing efficiency, Horween still prides itself on making things the old fashioned way – even if it takes longer and costs more.

As longtime fans and customers of Horween, it was a special experience to be invited by Nick to visit the tannery earlier this year. We sat afterwards in his father’s office to chat about his personal journey that brought him to the east coast and later on back into the family business. It’s a position that Nick treats with great reverence, and we look forward to seeing where he takes Horween in the decades to come.

Table of Contents

-

Instagram

@horweenleather -

Website

horween.com

Follow Nick

1 Background

Did you spend your childhood running around the tannery?

Definitely. We lived in the suburbs so I remember taking the train in, walking through the front door and catching that strong leather smell. My dad’s jacket always smelled like that too. When I turned 16, I started spending my summers here working on various machines or doing random maintenance. I’ve run a fair number of the machines so I can understand how they work and what they do – but nowhere near the level of our factory guys; they’re the real experts. They’ve been here a long time and have worked the same job so it’s natural that they’ve become so good at their specific tasks. But my summers here helped build my overall understanding of the process from start to finish.

What did you study in college?

I studied business, with a focus in marketing and finance. I met the woman who would become my wife during my college years. After graduation, we moved to New York for three years. She’s a dietician and was matched with Hunter College in New York; it’s like a residency but they call it an internship. We were hoping for New York, Chicago or San Francisco and she ended up getting into her first choice. She completed her yearlong internship and then worked for two years at a non-profit in the Bronx.

I decided to attend culinary school because I didn’t know what I wanted to do with myself. Cooking had always been something I wanted to do in the back of my mind, and when we moved to New York it was kind of the perfect time to give it a shot. I figured that I’d never have the time or opportunity to do this again. I studied at the French Culinary Institute in an intensive six month program where you’re cooking 40 hours a week.

What kind of restaurants did you end up cooking in?

I never took a restaurant job, actually. I staged, which means you work for free in various kitchens in the hopes of earning a job there – it’s pretty standard industry practice. Even though it was mostly prep work and not a lot of actual cooking, I learned a lot because I got to see up close how all these different kitchens were run. I received a handful of offers that I was interested in but the hours and the money bummed me out. I wanted to be able to spend time with my girlfriend and have a normal schedule, and it became apparent that the lifestyle of a chef in the traditional sense wasn’t for me, so I began working as a private chef. I would cook meals for clients once a week: I sent a menu ahead of time and then I would go to their home and prepare meals for the week, package them and leave instructions. It was hard work; I’d have to go to the store, gather what I’d need, then schlep it around the city to go to someone’s kitchen that maybe had the things I’d need… and then do it all over again. It was a subscription service so I was cooking for the same people every week, thus I got a lot of great feedback to help guide me. I did everything from very fancy, elaborate meals to “I want you to make me 5 gallons of mac and cheese so my kids have something to eat every day.” Despite the hard work, I had fun – but what I didn’t like about the job was that there wasn’t much learning involved. It was just me looking things up and figuring out recipes on my own. I wasn’t working under an amazing chef who was teaching me new and innovative techniques.

How long did you do that for?

About 3 years. I kept the books and managed 5 other chefs for a business that we were all a part of. I had never done that before; it was all self-taught. It was fun because my days were always different and I got to learn a lot about running a small business.

What prompted the move back to Chicago?

It was a combination of things. We got married. It was 2008 and the economy was not great in NYC – as you can imagine, the first something somebody cuts when budgeting is a private chef. And more importantly, I felt like there was a place for me at the tannery for the first time. I never wanted to just come in and make myself useful; I felt like I had to join at the right time to really do something. Lastly, my wife also felt ready to move on from her job.

2 Horween

Would you say that Horween is doing pretty well?

Yes, we’re doing well overall but the business is cyclical; for instance, this year is slower than last. Retail in general was a struggle this year for most of our customers, which in turn travels back to us. We had some really slow years when I started in 2008. At our biggest, the company employed 300 people and at our lowest point we got down to 120. The last two years have been really good for us, though, and we’ve been able to bring back about 40 employees.

I assume it’s been aided by the reputation you’ve earned in the past few years amongst a new kind of customer.

The whole ‘Made in America’ thing tuned a lot of people onto us, which was really nice. It was a weird benefit of the recession, since people wanted to know where they were spending their money and they wanted to buy something that was made well and was going to last. Our operating principle has always been this: if people can tell the difference between our work and that of others, then they will pay more. Our stuff is more expensive for sure.

And it keeps going up, right?

We are tied to the price of the hide, and it’s a commoditized market. Two years ago, the hide market was crazy so our prices had to go up, but they have since leveled off. Our single biggest price component is the hide itself, and good hides are not cheap. Probably 60-70% of all hides in the US go to China; there’s just no industry here for it. The whole tanning industry in the US is under 5,000 people now. There are only about a dozen tanneries left in the US; there used to be 30 in Chicago alone. All the medium sized tanneries went out of business and all the big ones went overseas. We are all specialists now.

There’s a fascinating mixture of new and old on the factory floor. You’ve got century-old equipment and processes running right next to modern machines. What’s the process like in deciding what needs to get replaced and when?

Long and very time consuming. We just got a new buffing machine last week; the previous ones were in use for 60 years. We were limited by those old machines though, as each one could only do one thing. We did a lot of research and even found some tanneries that were using that equipment and brought our leather over there to test them out. All the machines are made to order so that gave us an idea of how we needed to adjust it for our space and our leather.

Can you give an example of a process that’s stayed manual?

Sure, when we swab the dye onto chromexcel. You can roll or spray it on instead of painting it, but we feel like our process is better even though it takes much more time. We like to use many thin coats which we feel build the color up and gives a lot more depth that will age better. It almost has a glow to it.

So for a family business that is still running many of the same recipes that have been in place for decades, is there still a lot of R&D happening?

Always. Because we are tied to fashion where people always want different stuff, we are constantly trying new things – sometimes it’s totally new and other times it’s just our version of something else we’ve seen that we feel we can do better. All of our work is custom. There’s development happening all the way until production; a customer will want something we make but with specific parameters that differ from the current leather on hand. There are tanneries overseas that try to knock us off all the time.

How do you deal with that?

We’re fortunate because even though they’re knocking us off, they’re not using the same material or taking the necessary time to do it right. Some tanneries have popped up because we can’t keep up with demand; I’m obviously biased, but I don’t think their output is as nice. They won’t do a lot of what we do by hand, which is what makes our product special.

I was at an embossing plate manufacturer in Newark and he was saying that he loves us because about every 5 or 10 years someone comes in and says, “I know how to make football leather, I just need you to make me the the embossing plate.” In other words, they’re trying to buy the plate that gives the leather the pebbled pattern that goes on footballs. That’s our single biggest product, and Wilson is our biggest customer. We’ve never patented our formula because after twenty years it becomes public domain and anyone can use it. We’ve done it the same way for 70 years.

So you rely on the fact that if somebody puts your product side to side with another they can tell the difference?

That’s a big part of it. I think that on the shelf, things sometimes look similar but once you put some time into the product the difference is noticeable. I mean, it’s the same for denim: the good stuff looks better as you wear it, and the bad stuff looks worse.

The good stuff looks better as you wear it, and the bad stuff looks worse.

3 Fitting In

You said earlier that in deciding to move back to Chicago, you finally felt like there was a place for you at the tannery; did you feel differently after college?

I just wasn’t sure what I wanted to do. My father always told me that there would always be a job here if I wanted it, but if I didn’t want it, that I should pursue whatever makes me happy and am passionate for. I always knew I wanted to try something else beyond leather because I didn’t want to just come to Horween and wonder for the rest of my life if I should’ve tried something new. From the beginning, though, I promised myself I would at least give full time work at the tannery a shot at some point.

I love it here. I feel a lot of pressure from my ancestors in the sense that they all really worked so hard to get it to where it is today. For me to not to do the job justice would be wrong.

What are some useful things you learned from your time away from the family business?

The biggest, in my opinion, was how to deal with people. If you can successfully deal with certain types of New Yorkers, then you can deal with anyone – they expect a lot and they have no time to wait. Going from trying to satisfy someone with food, which is a very personal thing, to selling leather is very different. But I try to make us as available to the end customer as possible. I think that’s important to customers and that it sets us apart.

When you came back, what did your father want you to get involved in?

He kind of gave me free reign. He gave some ideas, but nothing was set in stone. At first I would take sales calls and would have no idea what I was doing. I was pretty nervous, but had no choice but to learn. My official title was “Director of Quality Control.” I mean, quality is our number one priority as a company, so to make me director of that was intimidating! I took it seriously, though, and spent a lot of time learning about how our product should look like at any given step of the process.

Did you feel like you would have to earn the respect of everyone here?

Of course, and I still do. When I started at Horween, my nightmare was to simply be seen as the boss’s son. There are a lot of people who have worked here for longer than I’ve been alive. The first month I was here, I noticed that one of our right-handed workers had his trash can on his right side. I figured that it might be easier for him to have the trash on the left so that it’d be closer to his left hand after he trimmed the scraps off with his right – so in the name of efficiency, I went up to him and suggested that he move it. He had been working for us for 37 years at that point.

He looked at me, paused, and said “I’ll try it your way” as he slowly moved it over. Within 45 minutes I saw that it was back to its original place. Now, when I see someone doing something I ask why they are doing it so that I can understand, instead of just telling them to “do it this way.”

A big part of your job since you came on board has been to educate customers with information direct from the source. How did product questions get answered before you came on board?

The channel wasn’t there. For the longest time, the only way to get ahold of anyone at Horween was to pick up the phone and call. Reddit, Styleforum and other online communities made it really easy for us to reach a large group of interested consumers. This was important because over the years a lot of misinformation had built up – and there still is – but that misinformation has decreased drastically because we can now help shape public knowledge. And then you get to the point where some people know the correct answers, and they can help spread the information organically.

A lot of tanneries don’t take that time to interact with customers. Maybe you do because you make a product that is desirable by a high-end male customer.

It’s a combination I think. A lot of the bigger tanneries make a commoditized product, like your standard white athletic footwear leather – there’s a lot of tanneries that can make the same product. We’re making something that no one else is really doing anymore. That wasn’t the case 50 years ago, but today no one else is making chromexcel, cordovan or football leather the way we are. Whenever we develop a product for the first time we want to make something that isn’t already on the market. We aren’t going to compete on price so we need to make something that is special, better, or just different.

We aren’t going to compete on price so we need to make something that is special, better, or just different.

You may not compete on price, but you do provide advantages over overseas tanneries, one of which being that if I started a leather brand I would have access to Horween, right?

You would. There are some things you wouldn’t have access to, like cordovan – I mean, we have a hard time fulfilling the shell needs of current customers. We get a lot of big fashion brands come in and say “We need black cordovan and a lot of it” and we’ve become unpopular with them because we have to say no. We’re not going to cut off Alden for 3 months to fill that order; Alden has been with us for 90 years and they are real partners. People may say we aren’t accessible because we are comparatively slow but anyone can come to us and get most things that we make.

When you see the kinds of end products that can be made out of Horween leather, does that motivate you?

Yeah, it’s inspiring. If anyone is putting that much care into their work, then the least we can do is give them the best leather we can. We really try to take care of our small customers. If we are 10 days late on an order for a small customer, then they aren’t working – whereas if we are a couple days late on a big company they probably have other things they can still be doing. I do think that this is something that gets lost on many suppliers. You can’t get big without starting somewhere, and we try to remember that when we are working with small brands. Relationships are very important.

4 Favorites

We asked Nick to bring in a few of his favorite items that are made out of Horween leather.

This is a Rawlings Heart of the Hide baseball glove that my dad gave that to me when I was 12. I was never an amazing baseball player, but I played growing up. As a kid you don’t always have a grasp of what leather turns into, but when I received this, it was one of the first times where I was really like “Oh wow, we actually make pretty cool stuff.” This is made of our baseball glove leather; we have a loyal following of customers who love it, especially in the collecting community. It’s a small piece of our business now because our leather is traditional: it’s tough and rock hard and you have to break it in. People now want a glove that’s ready to play out of the box. Plenty of other manufacturers can do that so we choose not to; and we like the old fashioned way. A lot of the pros do too.

This is probably the newest product on the table. It’s a 3-piece shell cordovan belt with a sterling silver buckle made by a German manufacturer called Kreis founded in the 60’s that has a factory outside of Frankfurt. Shell cordovan isn’t long enough to make a single piece belt out of, so you have sew together 3 pieces – sometimes 2. The owner’s name is Bernd Kreis and his father started the business with belts, but they’ve since branched out into bags and other small leather goods. His attention to detail and skill is amazing; I don’t know anyone doing it better. We were walking around the factory, I spotted it hanging up casually said “That’s an awesome belt” and then kept going. Bernd came up to me later and said “You forgot your belt” and handed it to me. I brought it home and it was too big, so I sent it back and he cut it down for me. He couldn’t be a nicer guy. It’s hand stitched on the outside near the closure; amazing precision.

Last year, we came across some beautiful deadstock vegetable tanned calfskin from 1949. Unfortunately, the specific recipe to recreate that leather has been lost so we can’t reproduce it ever again. We took what we had and sent it to Kreis to make something out of, and they came up with these beautiful slim billfolds.

The first wallet is a bilfold made of old calfskin that is so wild. There were three colors available; this one is the orange. I think this made was a company that has since gone out of business but the leather is from the 40’s. We called it Timber Tanned Calf.

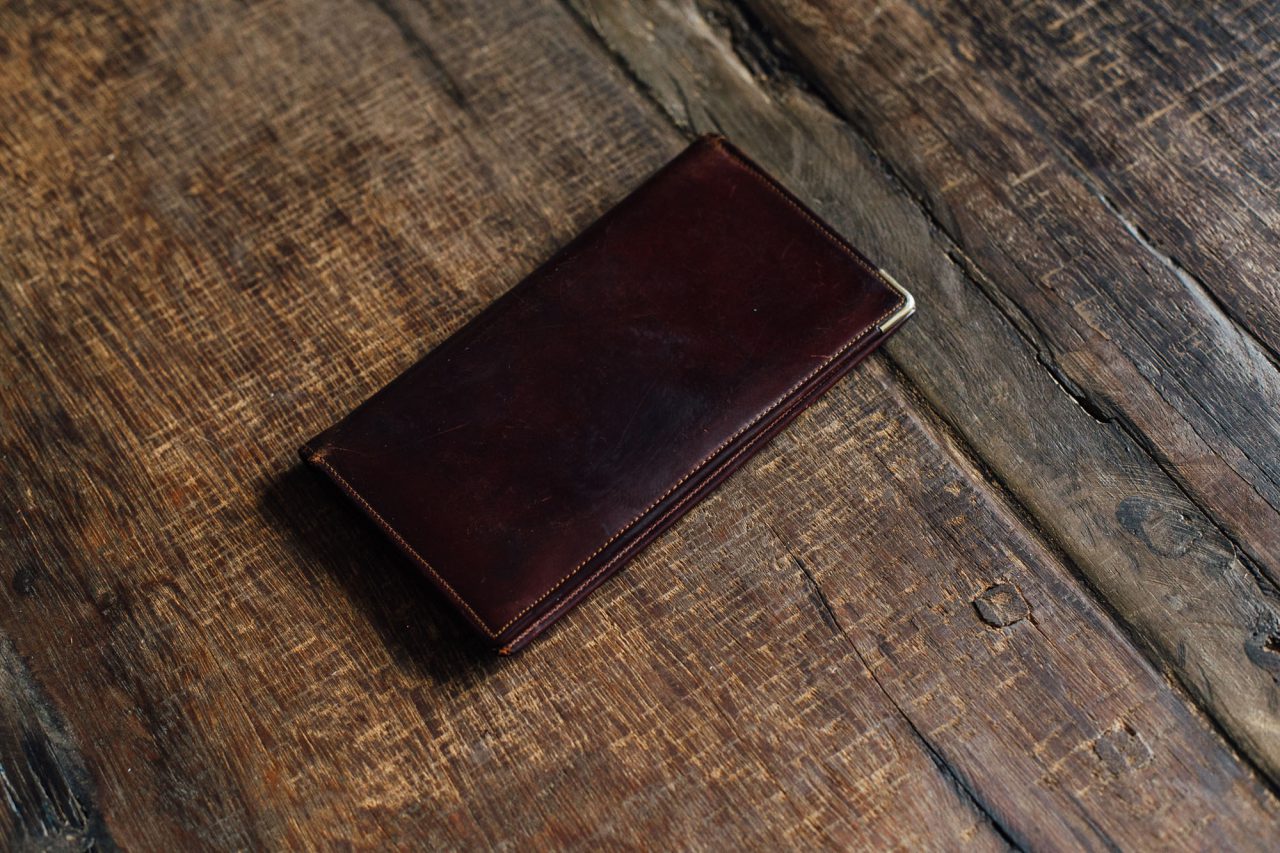

Next up is my daily wallet. It’s made by Ashland Leather, which is actually owned by two production managers here who make wallets and belts on the weekends. I have a lot of wallets but this is the one I keep coming back to. This was natural shell to start.

This checkbook was my grandfather’s. All his stuff was still inside when I found it, so I left it in. Like this shred of paper that says “Al Cox, Manager, United Airlines, Boise” – he must’ve taken that name down to file a complaint or something. There’s also an old Marshall Field’s credit card and a selective service system card for the draft. Sometimes I have to check to make sure it’s all still in there because I don’t want to lose any of it.

The shoes were my grandfather’s, same as the checkbook. When he passed away, my Grandmother was getting rid of his stuff and found them in his closet. I wear them all the time. They are Whiskey Shell Alden Saddle Oxfords – a pretty classic American shoe. They’re so comfortable too; I have not been kind to them at all and they still look great. This is what you talk about when you say shell looks good forever. They need a new heel but I’m always nervous about sending them back because sometimes they re-stain them or recondition them to make them look new, which I don’t want. I’m not going to take that chance.

The watch is a wedding gift from my wife and the band is made by First Settlement Goods in Madison, WI. He is associated with the Context guys, and his work shows great attention to detail. The strap is all hand stitched and if you look at the backside, you can see he split the back off a black shell to make the liner green with the natural top.

5 Conclusions

Now that you’ve been back in the family business for some time now, does your father understand the importance of what you’re trying to bring to the table?

I think he does. When I first started and I was trying to make us as available to our end customers and answer their questions, he would try to kick me out into the factory – which is really important to have eyes on and be able to identify how things should look, and what is wrong and right. That’s actually helped inform my ability to educate our customers. But while he might not have seen it previously, he definitely sees it now. Nobody took the reins on the communication end before.

Does part of what you do – growing the Horween brand – come off as strange to some of the people that have worked here for so long?

Perhaps. I think it’s because they are very focused on what they are doing. We are a union shop, so when someone joins the company they will head to a department and stay there and eventually train others. They may have a very specific view of what we do, and that’s through no fault of their own but just a function of the manufacturing process. I think that what I do for the company does come off as strange to them. Because of that, I try to take final products onto the floor to show them what they are making, kind of like when I saw my first Horween baseball glove. Giving them context is important and allows them to take further pride in their work.

What are some of the more difficult challenges you’ve encountered while working here?

It’s personnel – and not our current staff, but rather finding someone that can fill the void if a valued team member retires. I think it’s a function of America becoming a service-based economy now; there isn’t the same pride in manufacturing as there once was. Instead, we have a “I’m working in the factory so you don’t have to” sort of mentality. Horween is always thinking about needing personnel to move forward.

What sometimes happens is that an individual who’s been in the industry for awhile will move to Chicago or relocate from another tannery, and contact us for work. When these kinds of people come in for an interview and turn out to be good at what they do, we will always find a place for them no matter what. For instance, when Gutman from across the river went out of business, we hired a bunch of their guys – and they are still here to this day. It’s important.

You became a father this year. What kinds of adjustments have you made to the way you work?

Less travel, mostly. In the past I was traveling often, but now I want to be home more, because it’s so much fun hanging out with my son. Overall, I’m more strict with my schedule because I want to see him at the end of the day. My workload hasn’t decreased, but I’ve just had to work harder on my efficiency and planning. It takes discipline in this business, and especially at this tannery, because there is honestly an unlimited amount of work you can do. For instance, we have plenty of old leather stock sitting on the racks; we don’t know what’s there but we need to identify it, categorize it and then try and sell it. When I first started working here, I never knew where to start each morning. I had to learn over time to approach tasks to the best of my ability and to be willing to accept that I did my best that day, even if everything didn’t get completed. I still need to keep that in mind now.

What do you want your legacy to be?

That’s a heavy question. What’s been good about Horween is that everyone who comes in sort of puts their mark on it, updates things carefully, expands or cuts back on certain things, and then passes it along. I’m not interested in changing that system because I think it works really well. I’m lucky I get along with father – we are very different and it’s a good synergy. I’m always trying to make him proud. Anyone who is in a family business who doesn’t feel that way is not all the way in.

It’s all about my family as a whole: not only having the ability to do the things I want to with my wife and child also affording them the ability to do what they want to do. In other words, being comfortable and creating opportunities. One day I want to tell my son that I’d love for him to work here – but if he wants to do something else, I will be his first customer.

I’m in it for the long haul. That’s the plan. I think that what we do is important, and whether I’m right or wrong about that, it feels important to me. It’s special and that makes it easy for me to come to work each day. There’s a lot of experience that’s been poured into making this place what it is, and I want to keep that going.